It has often occurred to me that the term “artist” is a rug under which a tremendous variety of dusts can be swept; all we have in common, it seems, is that we produce things meant to be seen. I believe, though, that each of us has her or his own aims in picture-making, and I assume that they all have equal validity, at least at the outset. In our world, the only possible answer to the question, “What is art?” is, “Whatever someone declares to be art.” Whether it continues to be art after it leaves the artist’s hands is, of course, the final verdict.

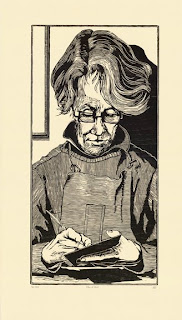

I’ve always been one of those artists who respond very directly to something in the environment—a landscape, a building, a gesture, a face. I used to say that I looked for an “Aha!” moment, something in the subject that expressed an ineffable quality or state.

But maybe that’s a cop-out. Recently, while working on my portrait project, I realized that what I look for is the metaphoric moment—that is, the moment, or the pose, or the composition, that lifts the subject (whether it’s a friend or a boulder) beyond the particular, so that the friend or the boulder comes to stand for more than itself, or, rather, comes to stand for both itself and for more than itself. You can walk down to the creek and identify the very boulder that I drew, but you will see that it represents both that particular boulder and something of the essential quality of boulderness, which is another matter; and both of those intentions exist together in the picture, but not necessarily in the boulder itself, which depends upon the artist to notice that universal aspect of its being.

I saw my friend Heather one night at such a metaphoric moment, when she entered the Metro car that Ellen and I were riding in. We were sitting to her right, and she turned leftward and walked up the aisle. She moved gracefully, standing tall among the seated uncaring travelers, and the sight moved me somehow. Over the next few years, each of my sketchbooks found me returning to a sketch of that sight, of a woman—well, of Heather—walking up the aisle of the Metro car on a winter night, graceful in the lurching train with the blue night outside and the passengers absorbed in their own lives. Years passed before I realized that the subway car was a contemporary incarnation of the medieval Ship of Fools, and Heather an embodiment of the grace and nobility that so often passes unnoticed among us—and still, it’s just Heather, really Heather, on a cold night, in a swaying Metro car.

--Max-Karl Winkler